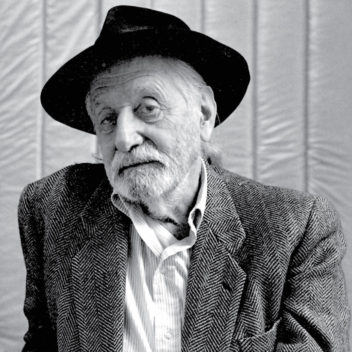

Emotions in Glass Ettore Sottsass

When you design glass objects and hope to make them, or hope someone will make them for you, you go through roughly three exciting moments. The first is when you think you’ve got an idea and think–or flatter yourself–that the idea really is an idea, that it really is a strange apparition, somehow emerging from the general confusion of ideas, which actually boils down to nothing, to the nothingness that was and suddenly is no more–because the idea has occurred; a nothingness–as has often been said–that has suddenly been enlightened.

The second is when you see that the glass, or its design, is about to be turned into glass. You know it is going to become glass, but you can’t yet make it out. You see a sort of ghost of what the glass will be, a limp, shining and colorless ghost, red-hot, untouchable and elusive, as most ghosts are–they say–like flames, fire, and the light of fire.

I have never actually made glass with my own hands. I have never blown into the long blowing iron to make a piece of glass, and I don’t think I would even be capable of picking a glob of burning glass out of the lake of red-hot glass at the bottom of the boca del forno. I know absolutely nothing about these risks and pleasures, and I certainly never will know anything about these secret pockets of knowledge. I only stand and watch the people who do possess that knowledge.

I know absolutely nothing about these risks and pleasures, and I certainly never will know anything about these secret pockets of knowledge. I only stand and watch the people who do possess that knowledge.

The second especially exciting moment comes precisely when you go into one of those enormous rooms with their white, warm, and silent air; warm on account of all the heat that comes out of the furnaces where the glass is soft; and silent because the men who work in those large white rooms wear tennis shoes or maybe special slippers, and talk in low voices. Perhaps they don’t even speak at all, because each man knows so clearly what he has to do that there is no need lo talk. In those big rooms, small clusters of silent men move around the bright and colorless glass as it begins to take shape. As in the ballet of a magic rite, the men come and go, squashing and stretching the glass, inflating and cutting it, carrying lumps of it and slicing bits off it, drawing threads and attaching other morsels, twisting tubes and bringing in wood, throwing water and performing an enormous number of unwavering, miraculous gestures and all the time holding the glass in midair while it slowly acquires form. Those men in tennis shoes, those men who make no noise, have to keep the glass forever in midair, because the soft glass always likes to drop onto the ground, maybe because glass originates from the earth–from sand and dust.

When I go into those big, white, very hot rooms, with the shadows of fires dancing on the walls, and the men’s eyes focused on the idea that a piece of glass must be made, that the glass has to be transformed into an object, that the glass will have a color, a measure, and a weight, that it will have a sense; that it will pass from one hand to another, from one space to the next, I gape; and if that glass on which all those men are concentrating their bent, attentive, lost gaze, is a piece of glass that perhaps came into my own head, then the surprise takes my breath away. I stand there open-mouthed like an idiot and ask myself:What’s happening? How is this possible?

To tell the truth, I don’t quite know how a thought that came to my mind about a piece of glass and only existed as a thought can sometimes become a drawing. But then the drawing becomes glass–an object that can be touched, weighed, and broken, or put away you can’t remember where–perhaps it’s been stolen–but no, it’s turned up again.

The passage from the drawing to the glass that exists only as glass always seems a miraculous one. So miraculous that I don’t really know where I come into the picture at all, since I’m not somebody who works miracles. Then I remember the men in tennis shoes, the clustered silent men who possess the wisdom, who know the rules and the boundaries, the secret tensions and hardness and timing, who know all the temperatures and weights and everything there is to be known about how to look at a drawing and turn it into glass. lf they weren’t there, would my glass objects be there? Would they be the way they are? The third moment is, of course, the triumphant one. Although not always. There are times when the glass comes out of the muffle, from the cooling tunnel, in broken bits. But nearly always the glistening molten glass has agreed lo let itself be cooled and to show its real color. AII this however has to happen slowly, very slowly, very very slowly, for hours, maybe whole nights, maybe days on end–you have to be patient. In the end, though, the glass is there. It comes out of the fire all clean, intact, bright, and perfect, exactly as you thought it would and maybe even more. At last the glass is there and can even be touched.

When I designed my first glass objects, about twenty-five years ago, I had already done a lot of ceramics. My first glass objects were done in Tuscany and I think those first glass pieces done for Luciano Vistosi were deeply affected by my earlier Tuscan experiences. I was trying then to design very simple things. They certainly were not minimalist, an existential choice of no concern to me. I wanted to design things that would somehow get me back to the origins of language, to that very mysterious time when the curiosity of untamed man was certainly not at its minimum but rather at its maximum. I’m talking about the period when untamed men were trying desperately, with signs and speech, to design an identity for themselves among the animals on the planet.Twenty-five years ago, and perhaps even now, I was trying to rediscover a fragment of those deposits of dust from history, fragments of the sandstone rocks that can still be found here and there, in abandoned quarries, and are a record of the very slow stratification of the figure of human essence.

I was not trying then to design some sort of absolute, some sort of representation of the divine, or any–long since lost–purity or any metaphysical perfection. I was trying–at least trying–to recapture a trace of that modicum of archaic curiosity or necessity, not of desire, that survives in our earthly destiny as men. Too ambitious?

At the end of the Sixties and during the Seventies, problems–in general–multiplied tenfold. The so-called industrial civilization, which was supposed to make us all happy and make better persons of us all, perhaps even aesthetes–and then the so-called postindustrial civilization and all those other posts, post etcetera-industrial civilizations, I’m not sure whether by destiny or by choice–began to define themselves as more and more introverted cultures, more exclusive and organized around themselves, more and more cryptic cultures, more lonely, more distant, increasingly deaf to the fragility of human existence. And the fragility of existence has not disappeared, on the contrary perhaps it has increased. The language, the logic, the codes that carry the new cultures are more or less hermetic and have now become pretentious languages, logics, codes. They emit no light.

During the ’60s and ’70s, entire young and not-so-young generations got scared when they sensed what was going on. They escaped in various ways: some in order to hide, some to avoid being around, some not to be involved. Some, who were really afraid, went into the woods and some tried to find time to understand what was behind everything that seemed so exaggeratedly chrome-plated.

Some, who were poets, wrote poetry and some wrote songs; some printed books and booklets, some took photographs, and some, who were destined to do drawings, drew.

Some of those people had an irresistible urge to see or even only to look for that modicum ofarchaic, bare necessity which might still be regained beyond the great lie announced by industrial culture, beyond the big, unfulfilled, promise of general happiness; beyond the ever-planned and by the unbearably boring mannerism that institutions pursued and continue to pursue. There were a few attempts to find alternative ways out.

Perhaps it was this constant effort that led some people in the profession to the trials and errors, to the disasters, hopes and ideas that later went–for example–by the name of Memphis.

The first real glass objects I designed for Memphis and produced with my friend Gigi Toso were vases of more or less normal shapes, already seen and foreseen. I had altered those ancient forms with surface variations, with more or less unexpected or disconnected external additions. The attempt was to get away from set codes. Perhaps only the color combinations were unusual: they certainly played an important part, by accelerating the sensorial perception of the object rather than echoing other possible withered metaphors or symbols.

It took a good deal of work and time to realize how much erotic potential could be expressed through glass, to understand just how far working with glass demands the attention of all the senses: a very special attention to thickness, distances, weights, colors, transparencies, overlapping transparencies, and mixtures of transparencies; and then also to understand to what extent glass creates a special awareness of its fragility. I’m talking about what glass itself asks for, which is to be treated with slow, precious gestures. In any case, even those gestures start from a possible sensorial rituality. With all this on my mind, I grew agitated when I started designing the second series, made for Memphis, again with the help of Gigi Toso. A good-natured and patient man, he was particularly patient when I told him the glass pieces I had designed would need glue to hold them together. At Murano as far as I know, the idea of using glue was nothing short of scandalous, and I think that for the true, classic masters of the art it still is. Nevertheless, for my glass objects, glue was used to hold pieces together. I also thought this idea of making pieces and then putting them on top of each other and attaching them to each other had come to me because I am fated to think as an architect, because as soon as I was born my father, who also was an architect, put a pencil in my hand. As if to say I was bound to become an architect. And that’s more or less the way it went. Since Memphis, since I designed that second range of glass objects, I have always thought of glass made of pieces put together either with glue, or jointed or fitted into a support, like the latest ones designed for my friends Marino and Marina Barovier and Bruno Bischofberger. This idea of designing glass with pieces put together in one way or another–pieces of different colored glass, different thicknesses, opacity, and transparencies, of different sizes, shapes, and origins–allowed me a great freedom of design. Most of all, it gave me an infinite catalogue of real, sensorial pleasures. It threw me into the open arms of glass as erotic material, enabling me to recount long sensorial adventures. It became possible to mix colors in the least expected combinations, to produce new and unlikely electric states by matching glass with wood, marble, and iron. I could imagine unpredictable balances of structures, and walk within the subtle realm of breathing and rhythm. In any case, all those trials always concerned exercises, movements, juxtapositions, collage, and acrobatics, executed with legible figures which led to a more or less abstract, sensorial whole. For a long time I stayed within the field of neoplasticist maneuvers–if I might so call them that–exercises in colors, forms, figures, and rhythms that live on nothing but themselves and never trespass on memories, nostalgia, symbols, enigmas, or literature.

Then, getting older, perhaps through one of those mysterious bits of information that reach us silently from the movements of history, I began to recognize that by now I certainly can’t imagine myself as an abstract being, a being that tries to live by abstractions. As the years go by I feel more and more as if I were built out of a very complicated chemical mixture in continuous agitation: a chemistry of memories, nostalgia, fear, and vital energies, of hopes and aggressiveness, sacrifices, names that come and go, exhaustive answers that fade away only to pose other questions. Sometimes I think that if I design something in glass–and not only in glass–I may also try lo leave some trace, some sign of this new perception that gives me perhaps a broader, certainly more complex, definitely less conceited idea of existence. Perhaps now I can leave some signs, at least some signs of affection, for all those ghosts drifting in from the past and from the future to crowd my time. That’s what I have tried to do in the latest glass objects, the ones done at Venini, for Bruno Bischofberger and in those done at Cenedese, for Marino and Marina Barovier.

Ettore Sottsass

Translated from Italian by Rodney Stringer