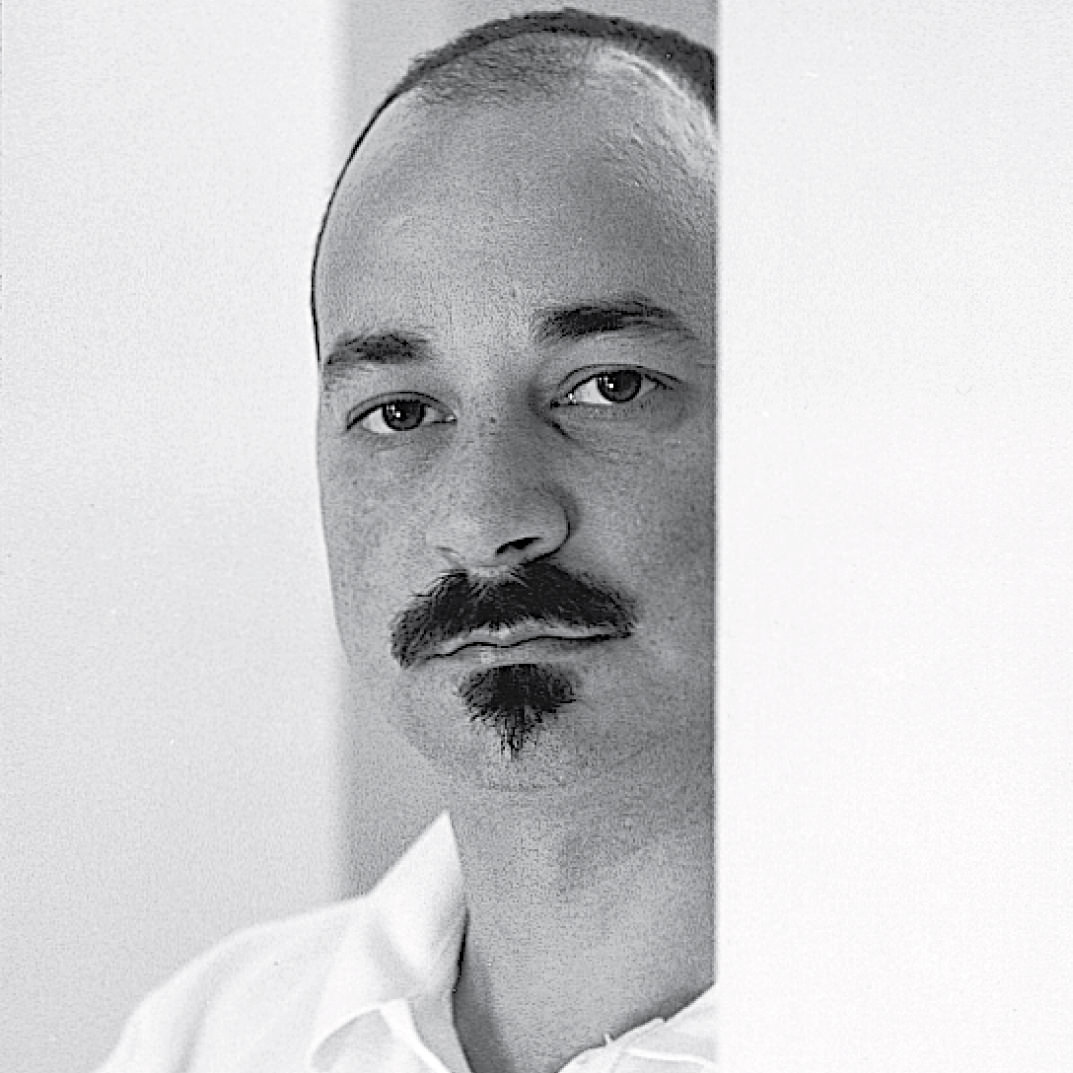

Open Letter Cristiano Bianchin 1963–

Dear Nancy and Giorgio,

You have asked me to share my thoughts on glass, and I am happy to accept because it gives me the opportunity to analyze my however brief experience with this extraordinary medium. I have decided to do it with this open letter, opening myself as you have opened to the world your collection of twentieth-century Venetian art glass, which you have put together with great passion and of which I am now part.

Personally, I think that I approached glass almost accidentally, but the results make me sure that there must be a link between the randomness of an unplanned action and the multifaceted curiosity that it can kindle. Glass is then curiosity; a game that has turned into painstaking analysis. I don’t think artists can express themselves through any medium unless they live in close daily contact with the place where the medium is brought to life. Even after many years, I feel a thrill every time I see those incredible furnaces. Here the crucibles with their red-hot hearts of molten glass are handled by men who live their life as in one of those circles in Dante’s Inferno, where the damned move among fire, iron, sweat, and curses, born to create glass out of humble minerals and become one with it. Glass is then a good vantage point as well as the most intriguing medium. I am fascinated by the timelessness offered by the furnaces, a dimension that opens into a contemporariness that is disclosed only to the most attentive observer and that sometimes sheds a less than magical aspect on glassmaking. I have always been very involved in experimentation, ever since I began working both with glass and in contemporary art, and the medium is of paramount importance to convey to the viewer the sensuality implicit in my art. My hemp installations, my drawings, and my glass pieces are essential and symptomatic components of the artistic research I have been developing over the years through the different media of visual communication. Right from the start, I have worked with glass as a possible form of evolutionary continuity based on the classic validity of the Murano glassmaking techniques that I contrast with forms whose plasticity is meant to be perceived through the eyes, through touch, and lately also though hearing. This latest development in my research is meant to create a sort of perceptual filter, guiding the viewer through composite sound back to the form, which is thus reanimated. From 1992 to 1995, the perception I had of glass urged me to actively employ the most traditional techniques. Blown glass with hot-modeled solid glass additions, murrine (a great passion of mine), incalmo, wheel engraving, stippling, wheel cutting and grinding, hot enamel applications, all were experienced as something to be tried. I felt, and to a certain extent I still feel, like someone who opens an alchemist’s recipe book full of the secret formulas carefully recorded by some long-gone glassmaker. And yet, I was not entirely happy with the result. My dissatisfaction was not directed at the forms I was creating, but what I was striving to achieve was an aesthetic and conceptual improvement in the forms themselves.

In late 1995 I changed the direction of the evolution of my forms, steering it towards a more precise aesthetic research, in spite of the problems this involved. The forms named Nidi (Nests) were conceived as mineral architectures, whose surface, imagined as the careful and detailed “inscription,” or a renewed “architectural description,” serves an emotional, tactile condition dictated by the necessity to lay a sort of skin over the glass body, on which to leave clear yet sensual marks, animating it with an opposite and rough material like hemp. To these sculptures without a base, I added other pieces that I called Semi (Seeds), Fusi (Pods), and Nidifusi (Nestpods), sometimes placing them on beds of peat or clay, the natural elements on which these forms germinate. The installations represent an indefinite place and time, and sometimes even give a sense of displacement, as if this nature inhabited by artificial bodies was coming awake after an ancient sleep, re-emerging from a state that is life and death at the same time.

Between 1998 and 2000, new ideas penetrated my research, originating the Riposapesi (Resting Weights) and Canestri (Baskets). These forms are the result of the evolution of the Nidi, and I consider them as an essential analysis of the possible transformation of glass into “something else.” The story they tell is a disquieting one, and the blown glass, either black or in saturated colors, is synthetically austere, in spite of the superimposed pieces that seem to be engaged in a sort of game. In some of these works I began to deny to the human eye the possibility of reaching the refined compactness of the glass, covering the whole surface with a thick hemp mesh that becomes once more a symbolic skin stretched over the glass bone structure.

Today I am trying to find as much time as possible to dedicate to my work in my studio in Venice. I look forward to seeing you again, and I thank you for the opportunity you have given me to express my opinion.

Best of luck for the exhibition.

Yours,

Cristiano Bianchin